Organic compost is a great natural fertilizer. Instead of buying compost, you can learn how to make compost at home. Start recycling your organic waste to supply your garden with nutrient-rich organic fertilizer and reduce your impact on environment.

Farmers across the world have been composting organic waste and plant matter. Composting is easy. Gardening enthusiasts can easily start composting kitchen waste and organic matter at their homes.

Whether you live in a suburban home or a tiny apartment, composting kitchen and organic waste can be started with very little space and some effort. Let’s learn how to turn your food waste and organic waste into organic compost in simple steps.

What is Compost?

Compost is simply decomposed organic material. Compost is made with organic material such as plants, leaves, shredded twigs, food waste, manure of herbivores (cow, sheep, goat, etc), kitchen scraps from plants, and wood shavings.

For horticulture and farming, compost is considered the best fertilizer for soil enrichment.

Compost turn clay soils makes them easier to work. Adding compost to sandy soils improves water retention. Organic matter from compost makes soil healthy and improves plant growth.

Composting recycles yard and kitchen waste. You enjoy twin benefit of improving your garden soil and save on the waste disposal cost.

Compost improves soil physical condition (tilth), reduces soil compaction, enhances aeration improving root growth and water penetration, boots water-holding capacity, and supplies plant nutrients.

How to Compost at Home?

Composting can be easily started at your home in your backyard. You need a pit or a bin to get started with composting.

Depending on your space availability, you can choose between composting pile (cool composting), active composting (with a bin or pit), and vermicomposting. Compost digesters (anaerobic) can handle most kitchen and food waste, but can be really smelly. Aerobic solar food waste digester (Green Cones) aren’t composters.

Before starting to compost, check for the applicable rules. Does your state, county or city allow composting? Are there any norms laid out for composting?

Composting in Pile

Composting is decomposition and breaking up of organic material. When you pile up your organic material, leaves and kitchen shreds, microorganisms start breaking it down. As the process is slow dues to less favourable conditions, this method called passive or cool composting.

A small range of microorganisms (mesophiles) that thrive in moderate temperature (68-113 °F or 20-45 °C) are responsible for passive composting in a rubbish piling. It is a slow process and takes about a year to compost using aerobic decomposition.

Passive composting can be done when you have open space where you can keep adding fresh materials to your compost heap. After about a year, your inner layer would be fully decomposed while the outer layer is just beginning to decompose. Harvest the ready compost at the bottom by removing the outer layers.

- Gather leaves, kitchen waste and other organic matter into a pile or bin.

- Sprinkle the waste pile with water and some garden soil.

- Build your pile till it’s 3-5 feet high, and avoid growing a taller stack.

- Food waste should be buried deep in the pile to keep them out of reach of pests.

- Composting will start and take about a year to decompose.

- Turn your pile every 1-8 weeks to move the outer layer inside for even decomposition.

- Once ready, you will be left with dark brown compost with an earthy feel.

If you have space, you can start a new pile when the first pile is about 3 feet high. Don’t build a tall pile to prevent compaction and allow air flow. If your pile doesn’t get enough air, it will begin anaerobic decomposition and emit foul smell. Turn the pile once or twice a year to speed up the process.

Slow composting can attract pests being to the decaying matter.

Composting With Bin

Most common composting is done with compost bins or pits, which yields compost in about 3 months. This method is called hot or active composting.

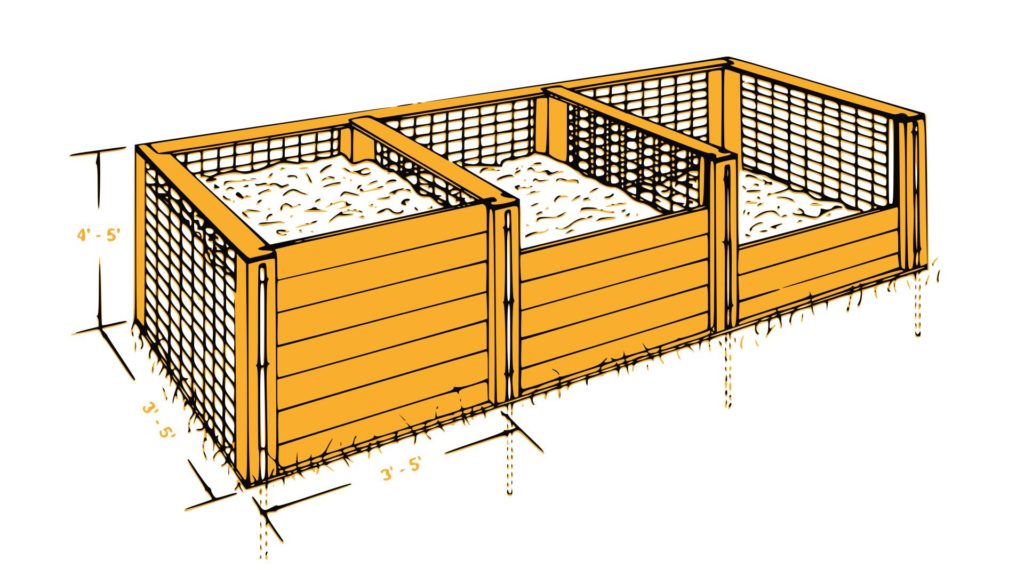

Hot composting is done in a bin, which can be a plastic container, masonry wall enclosure, wooden enclosure or a wire mesh enclosure. The ideal bin size is 3’x3’x3′ or 27 cubic feet, which support a broad range of microorganisms.

Open bins are made of wire, wood slats, or concrete blocks, and generally designed with one removable side using wood slats for easy access to compost. Most bins have three compartments for batch composting.

A three-compartment wooden bin can be constructed for hot composting. Alternative to wood are wire mesh, brick masonry and even plastic bins with perforations for air flow. You can learn how to make a compost bin at your home.

A pit dug in the ground is also used for active composting. For composting, dig a pit 3 feet deep by 3 feet wide.

Find a spot in your yard that receives plenty of sunlight, which helps keep compost pit above 110° F. Your compost pit or bin should not be too close to any house. Decomposition can emit foul smell. Choose a location at least 6 feet from your house and protected from flooding or runoff to surface waters or wells. Pick a location away from your kitchen garden to avoid contamination.

Hot composting can be done in a single batch or continuous pile. In a single batch, all the materials are added at once and left for composting.

Where organic material is generated in small quantities, continuous pile is implemented. Organic matter is added in the bin as it becomes available.

For hot composting, you need a mix of browns (carbon) and greens (nitrogen) in near equal proportions. Place a layer of greens such as kitchen waste, vegetable scraps, livestock manure, coffee ground and grass. Top it with a layer of browns such as wood shavings, dry leaves, paper shreds, cardboard, and straw. Add a thin layer of soil to introduce microorganisms and create a barrier. Keep repeating the layers till you reach 3 feet height.

Alternatively, greens and browns can be mixed evenly and put in the bin.

Water each layer to add moisture evenly. Approximately 40-60% moisture is needed in the pile. Your material in the bin should be damp (like a sponge after water is squeezed out) for proper microbial growth and decomposition.

When your pile reaches 3-5 feet height, it’s ready to be left for composting. Add a layer (3-5 inches) of brown materials at the top. Don’t leave greens at the top. Decomposing green materials attract pests and flies. Adding browns as the last layer blocks flies and foul smell.

A compost pile should be at least 3 feet in length, breadth and height for heat preservation and insulation.

Once your composting pile is ready, the mixture of carbon (browns), nitrogen (greens), water, and air creates a great habitat for thermophiles (heat-loving bacteria and micorganisms). Once thermophiles start decomposing organic matter, the inside temperature rises to 130-170° F (typically in 24 hours) after the bin is filled. Temperature kills most pathogens and weed seeds.

As thermophiles break organic matter, heat is generated and water is evaporated.

Once the waste is processed by thermophiles in 2-4 weeks, temperature starts dropping. At this stage, sugars and starches are broken down. Tougher compounds such as hemicellulose and cellulose remain unprocessed.

Turn the waste before the center drops below 100° F. Turn the outer layer to the core so that the microbes have fresh material for consumption. Turning also provides aeration and speeds up decomposition. Add water to the bin if the material becomes dry.

Keep checking the temperature, turning, and adding moisture when necessary. When the compost is ready, your material would have reduced to about 50% of the original volume, leaving behind dark brown earthy matter.

Once thermophiles are done with the material, temperature will not increase. However, the compost is not ready yet.

Let the compost pile cure for two-six weeks. Mesophiles, or microbial organisms that thrive in moderate temperature, will start working and complete the decomposition for tougher cellulose and other compounds.

Keep your compost pile covered during rainy and dry seasons to maintain the right water level. Too much water prevents composting. Absence or little water also hinders in composting.

Here’s a quick look at the hot composting or active composting process for home gardeners.

- Prepare your compost bin and put a layer of soil at the bottom if not composting in a pit.

- Chop or shred your organic matter (plants, vegetable waste, paper, etc) into small pieces to increase surface area for microbes.

- Place your organic matter in separate layers of greens followed by browns. Alternatively, mix greens and browns evenly into one layer.

- Add a thin layer of soil to introduce microorganisms.

- Water each layer so that it is damp and contains 40-60% moisture.

- Repeat the layers till your pile grows 3-5 feet. Stop adding to the pile and start a new one.

- Add a layer of 3-5 inches of browns (saw dust, wood shavings, paper shreds, etc) on the top.

- Within 24 hours, microbes start heating up the core. Keep checking for the temperature.

- Temperatures in the center of the pile will be hottest and they will be cooler on the outer edges. Turn the pile when the center begins to feel cool to the touch.

- Add water to the pile if it becomes too dry.

- When your pile reduces 50% in volume, let it cure for 2-6 weeks.

- Dark brown earthy matter left at the end is your compost.

What to Compost?

Composting is suitable for organic matter. All compostable organic matter is categorized into green or brown. Materials with more nitrogen are termed greens. Most of these are fresh plant materials, such as grass, vegetables, fruits, eggs. Materials rich in carbon are termed browns. Such items include wood shavings, dry leaves, straw, paper, etc.

Here are common items that you can use for composting.

| Nitrogen (Green) | Carbon (Brown) |

| Grass clippings | Leaves, twigs, yard trimmings |

| Houseplant leaves | Natural fiber yarn, thread, string, rope |

| Hair, fur, nail clippings, feathers | Paper rolls (towel, toilet, gift wrap) |

| Vegetables, fruits | Nut shells (not walnut) |

| Coffee grounds, filters | Cotton balls, swabs |

| Tea bags, leaves | Dryer lint from natural fabrics |

| Egg and crustacean shells (rinsed) | Cotton, wool, silk, felt, hemp, linen, burlap |

| Old herbs, spices | Vacuum contents, floor sweepings |

| Flowers, dead blossoms | Straw, hay, corn cobs |

| Beer, winemaking leftovers | Newspaper, nonglossy paper |

| Juice, beer, wine, dregs | Brewery hops |

| Freezer-burned vegetables, fruits | Loofahs |

| Aquarium water, algae, plants | Paper napkins and bags |

| Seaweed | Sawdust, wood bark and chips |

| Herbivorous animal manure (rabbits, cows, sheep, chickens, horses) | Bamboo skewers, toothpicks |

| Pizza and cereal boxes, paper egg cartons | Pencil shavings |

| Paper baking cups | |

| Grains, cereal, crackers |

Some organic matter are not suitable for composting. Meat, bones, pet excreta, dairy products, fats, pesticide treated plant waste, diseased plants, facial tissues, diapers, plastic coated paper, large amount of wood ashes, coal ashes, etc. should not be put in compost.

Composting with Earthworms

Earthworms are used for composting kitchen waste and garden scraps. Vermicomposting (earthworm composting) turns food scraps into nutritious soil for crops and plants. This system has a worm bin with bedding. Composting earthworms handle the task of turning food scraps into compost.

Compost Digesters

Compost digesters are used for anaerobic decomposition of food waste, while Green Cones use aerobic decomposition for waste management (without making compost). Both anaerobic composters and Green Cones can handle most food waste — vegetable scraps, fish, meats, bones and dairy products — except high-fat items: mayonnaise, rancid butter, etc.

Curious to learn even more about composting?

Further Reading Resources: Oregon State University has a simple guide with detailed information. Read Composting and Mulching: A Guide to Managing Organic Yard Wastes, available for download as an e-book by the University of Minnesota. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources also has a great booklet on home composting.